Toshihiro Nagoshi has worked on some of the most influential games of all time, including Virtua Fighter and Shenmue. These days, he’s most well known for his work on the Yakuza series. We caught up with Nagoshi to learn more about his life, career, and why he thinks Sega should’ve fired him.

Toshihiro Nagoshi knows how to make an entrance. He’s seven minutes late after a smoke break, wearing a $2,700 Louis Vuitton jacket. Coy yet honest, reserved and flashy all at once, somehow, he fits his 30 years of game-development history into an hour-long Zoom call. It’s a story that encompasses childhood trauma, Yu Suzuki, and drunken meetings that turned into one of the biggest cult franchises in video game history. But it all starts far away from where he’s sitting right now in Tokyo.

Nagoshi grew up in the small, rural prefecture of Yamaguchi. When you talk to him about his early life, he doesn’t have a lot of positives to share. Nagoshi came from a poor household, his parents victims of sizable debt, and his father in particular had a gambling problem. Despite saying he recognizes that what he went through with his family was a necessary learning experience that got him to where he is today, he has a lot of complicated feelings about the household he grew up in.

Nagoshi says his younger life lacked direction, and that he didn’t really have aspirations for himself in Yamaguchi. He did, however, have one dream: He had seen Tokyo on TV, and something about city life appealed to him. After graduating high school, as the people he grew up with began getting jobs in their hometown, Nagoshi realized he didn’t want to live a similar life. He didn’t want his parents’ lives either. So, he left.

“Just to be honest, I grew up in a poor household and watching my parents, I kind of figured that staying [t]here and following in their footsteps wouldn’t necessarily lead to a happy life for myself,” Nagoshi says through a translator. “So, just being young and having a strong desire to get out and make a life for myself was one of the reasons that I went to Tokyo.”

Later in life, after working his way up within the game industry, Nagoshi returned to Yamaguchi to pay off his parents’ debt. Unfortunately, however, he says by the time he was able to do this both his mother and father had dementia, to the point they were unable to recognize his actions or appreciate what he had done.

“But I did hear later on from the people of the town that my parents, when they saw that I had an interview published in a magazine or saw me in the media, they would take my picture around,” Nagoshi says. “They would really proudly tell the townspeople about me. Hearing that really made me happy. Even though the money caused strains in the relationship, I’m 100-percent at peace with it now.”

Virtua Racing, one of the first games Nagoshi worked on at Sega

Virtua Racing, one of the first games Nagoshi worked on at Sega

In the 1980s, Nagoshi moved to Tokyo to study movie production in college. His timing wasn’t great, though, as the Japanese film industry wasn’t exactly a lucrative business. Looking unsuccessfully for a job in movie production, Nagoshi says he came across an opening at Sega. At the time, he says he knew Sega was a big company, and he thought there was no way he’d ever be brought onboard. He applied anyway, “For kicks,” as he puts it. Nagoshi wasn’t turned down, but in fact was hired to Sega AM2, a development team within Sega known in the ‘90s for its arcade and fighting games, headed up by legendary developer Yu Suzuki.

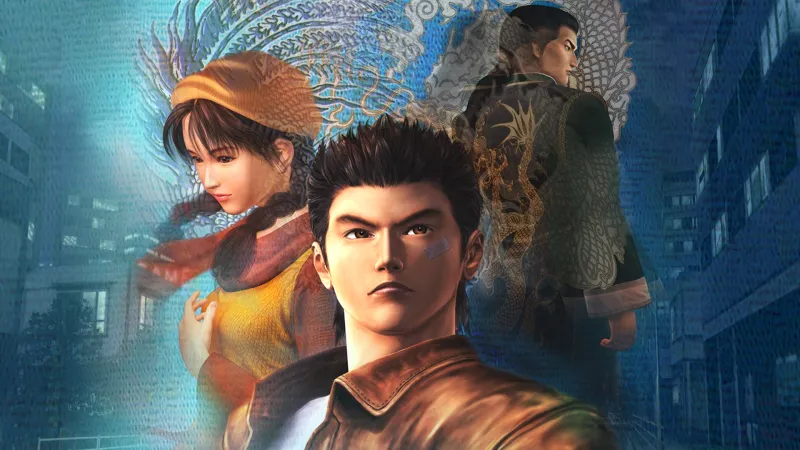

Having no formal background in game development and working with Suzuki, Nagoshi says his early years at Sega in the ‘90s came with a steep learning curve. On the other hand, he racked up an impressive portfolio, working as a designer on Virtua Racing, directing Daytona USA, and even working on Suzuki’s over-budget magnum opus, Shenmue, the most expensive game ever made at the time.

In the ’90s, Suzuki was not only a big deal in the game industry, he was a big deal at Sega – which perhaps afforded him and his team special treatment within the company. Nagoshi says the team was isolated from the rest of Sega, physically at a distance from its headquarters. The AM2 office even needed a special key to enter. “It was sort of irregular and a top-secret type of operation that was going on,” Nagoshi says.

“It was very strange, where even though he was part of Sega, the president of Sega would not know what [Suzuki] was working on at that time,” he says. “There were occasions where, every six months or so, the president and his entourage would come knocking on the door demanding to see, like, ‘What’s going on in there?’ And there were times that even then we wouldn’t show them what was being worked on.”

“It’s amazing that [Suzuki] didn’t get fired,” Nagoshi says, laughing, adding it’s amazing the entire team wasn’t fired along with him.

By the end of Nagoshi’s time with AM2, Sega wasn’t doing great. The Dreamcast, released in North America on Sept. 9, 1999, ended up being a failure for the company, eventually leading Sega to exit the hardware space entirely and focus on developing games for companies like Sony, Microsoft, and even its once-fiercest rival, Nintendo.

Shenmue

Shenmue

At the same time, Sega was restructuring its internal development teams, splitting them into eight separate semi-autonomous studios, each led by one of the company’s top designers. Nagoshi was appointed president of Amusement Vision, which would go on to make the Monkey Ball and F-Zero series for arcades and the GameCube. Three years later, in 2003, Sega restructured itself once again, merging the studios into four teams and inviting the heads of the three most successful studios to become executives within Sega. Nagoshi was one of those three, as was Sonic Team’s Yuji Naka and Hisao Oguchi, who later became Sega’s president for a time. Amusement Vision was merged with members of Jet Set Radio Future developer Smilebit, eventually becoming Sega NE R&D – or New Entertainment Research & Development – in 2004.

“Our first real challenge was how to combine the strengths of these two developing teams and make something new,” Nagoshi says. His solution was to come up with a game unlike anything either team had ever worked on; something completely new that would appeal to Japanese audiences. To brainstorm new ideas, Sega NE R&D would take company field trips to a place that would come to define Nagoshi’s career: Kabukicho, Tokyo’s red-light district, at one time the heart of the city’s yakuza activity, and the real-world inspiration for Kamurocho, the primary setting for nearly every Yakuza game.

“We all really liked to drink a lot,” Nagoshi says. “The discussions in meeting rooms are important to have in meeting rooms, but also, just being in a completely different setting where we’re just kind of casually having drinks, I felt, was a much easier way for me to communicate with especially the younger team members and have them feel like it was easier to speak out with courage.”