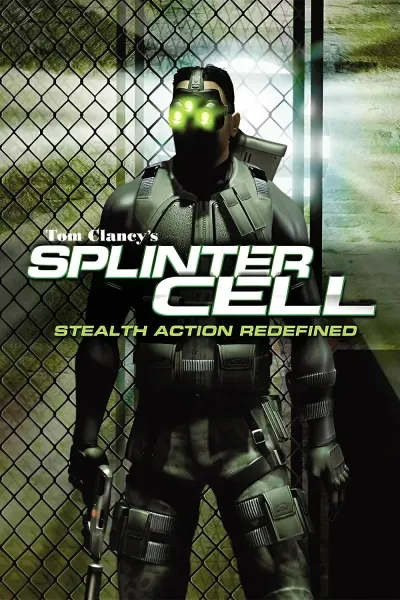

Splinter Cell’s star has faded. In the years since Sam Fisher’s last outing, 2013’s Splinter Cell: Blacklist, he’s made a handful of cameo appearances and even shown his battle-worn visage at a conference or two. And there is a remake on the way – of which we’ve only seen concept art. But by most measures, the franchise has been dormant for a decade.

Nonetheless, Fisher was once the lead of a game momentous enough to compete for sales with Halo, have Hideo Kojima’s Metal Gear Solid team taking notes, and find itself referenced as the graphical and technical benchmark of the early Xbox years. With two decades of distance, it’s hard to see the defacto mascot of novelist Tom Clancy’s video game offshoot brand as anything other than the embodiment of its ethos; the avatar of Clancy’s own stable of globe-trotting, no-nonsense, flag-waving heroes. But in fact, his wry, ironic wit and detached sarcasm point to more than just the tropes informing his character – they betray the fact that his creators couldn’t be further from Clancy’s type.

“One time I was having lunch with the guys from PAX,” says Ed Byrne, lead level designer, “and they were big fans of Splinter Cell. And when I told them this story, they were like, ‘Wait a minute, wait a minute, Splinter Cell was ironic? It was an ironic Clancy game?’”

Byrne recounted his memory of J.T. Petty, who wrote the script: “He was a sandal-wearing, vegan, NYU student.” Not at all the kind of guy who would keep a shelf of Jack Reacher novels.

“It was almost to the point where we just threw in all of these tropes to see what we could get away with,” Byrne said, “and every time we added more tropes, the more Clancy-like it became.”

Had Clancy shown any interest in the project, he may have objected, but Ubisoft Montreal’s work was in his periphery at best.

That a studio like Ubisoft Montreal circa 2002, still largely unproven outside of its work on licensed, kid-friendly games, could make a standout title in a genre it had never worked with, using a license much of the staff didn’t care for, with a team made up mostly of completely inexperienced developers is remarkable. That it helped cement a burgeoning genre and remained one of the top-selling Xbox titles for the console’s life is even more so.

“Seen from the inside, every game is a miracle,” writes creative lead Francois Coulon in an email interview. “Here, the planets [were] perfectly aligned.”

The story of Splinter Cell contains many such alignments, not the least of which is the unlikely pairing of, as Byrne recalls laughingly, “a bunch of bleeding heart liberals” and Clancy. Like any sufficiently complex video game, the seeds of its creation sprouted first in several different places. They came together only incidentally, through decisions and events happening separately and without connection. In the mind of a French artist dreaming up a world of floating islands, in a Paris boardroom over a game of Metal Gear Solid, in the offices of a North Carolinian animation tool company taking its first steps into a new medium.

Getting The Crew Together

For Nathan Wolff, it started in 1998 when he was looking for any job to get him out of his small hometown in rural Maine and into the big city: New York, New York.

“I don’t remember where. I mean, back then, it must have been in some print newspaper or something. I saw an ad for ‘video game designer.’ [...] I don’t know what moment of youthful confidence I had,” Wolff says. Despite no real foreknowledge about what the job might entail, he sent a cover letter. After an unconventional interview where Wolff had to invent and flesh out game scenarios on the fly, he was hired just like that. In a couple more years, he would find himself as the lead game designer on Splinter Cell.

“Looking back, it was totally insane," Wolff says. "I had no experience.”

He wasn’t alone, either.

Splinter Cell

Splinter Cell

“I was a new game designer, just fresh out of college,” says Ed Byrne, lead level designer. “It was all of our first gigs […] Even the senior people on the team, myself included, were first-timers.”

Whether Ubisoft intended to fill the ranks of a new studio with cheap labor by hiring green or foster innovation by bringing in untrained talent is difficult to determine. But the effect was the same either way. The small team that began work at Ubisoft New York was composed of mostly blank canvases. At first, it worked on licensed, child-friendly fare like Tarzan: Untamed. It wasn’t too dissimilar to the slightly older Ubisoft Montreal just to the north, creating titles like Tonic Trouble and Laura’s Happy Adventures – safe bets in the heyday of the licensed game era. Soon, however, an ambitious and promising project would arrive in their small, Midtown Manhattan office all the way from Paris.

The Drift

Earlier that year, Francois Coulon, eventual associate producer and creative director of Splinter Cell, was heading up a team in Paris to develop Ubisoft’s first shooter. Upper management hadn’t shown much interest in the genre before, but Coulon convinced Ubisoft co-founder Yves Guillemot to give it a chance after showing him some scenes from Metal Gear Solid. It did the trick; the idea was greenlit with a small crew.

In early 1999, Gerard Guillemot sent Coulon’s team to New York. It brought the beginnings of its new game, The Drift.

“In a sea of kid-friendly games, The Drift was the more mature sci-fi project that caught my attention immediately,” writes lead character artist Martin Caya in an email interview.

In it, Earth had burst apart, the remains of civilization built atop the floating vestiges suspended high in the sky. Populating giant airborne islands were retro-futuristic buildings, flying cars, clunky analog gadgets, and dynamically reactive crowds. The game’s protagonist wielded a hefty gun with an attached TV monitor, a manually winding winch grapple, and an old-school switchboard used to control its main feature: a video feed to take advantage of various vision augmentations and remote projectile cameras.

Dynamic, emergent, stylish – The Drift was supposed to be it all.

Splinter Cell

Splinter Cell

“The idea was that we could probably just pick the best gameplay mechanics and combine them into a game, and that would be The Drift," Byrne says. "But, of course, the problem is that you can’t really just combine a whole bunch of gameplay mechanics and have it be cohesive. And I think, ultimately, that’s what killed the project.”

The Drift was too ambitious for the inexperienced team at Ubisoft New York. When Ubisoft’s number crunchers looked at the cost of maintaining a small studio in downtown Manhattan, some of the nation’s most expensive real estate, the studio itself seemed a little too ambitious. The crew was offered the chance to relocate to Montreal and join the now 300-strong studio to its north. When it did, The Drift came too. It didn’t last long. Corporate told Coulon that a new IP was too risky. Now with full access to Ubisoft Montreal’s greater pool of resources and the company’s catalog of characters to choose from, Coulon was asked to retool The Drift into a pre-existing franchise. Ubisoft, of course, had no shooters to work with.

“At the time, all you could throw was Rayman’s fist!” says Coulon.

Without a character or property to guide production, the core team continued work on a generic third-person shooter, hoping something would eventually come along which might align with the work already completed.

“The head of Montreal Studio, willing to see this go into production, was coming to me every month or so with weird IP suggestions such as Pamela Anderson’s V.I.P.,” writes Coulon. The team even toyed with the idea of using James Bond. According to a 2014 article by IGN, a demo was created and used as a “shot in the dark attempt to impress the license holder,” but nothing came of it.

“And then, of course, when [Ubisoft] bought Red Storm and got the Tom Clancy license, everything changed,” says Byrne.

The Metal Gear Solid 2 Killer

A few years earlier, Clancy had enlisted the help of Cary, North Carolina-based Virtus Corporation, an animation company with a small video game division, to adapt his novel SSN into a video game. One day after its release, the new collaborators formed Red Storm Entertainment and went on to release a handful of Clancy titles that more or less came and went before Rainbow Six rocketed the studio into the mainstream. In the summer of 2000, Ubisoft scooped up the company to acquire the Clancy license.