Tim Schafer likes Star Wars. But as far as he’s concerned, Lucasfilm’s video games were the company’s greatest creative output. In the early ’80s, George Lucas’ burgeoning computer division explored a few forms of entertainment outside of the movie industry. In 1984, the company released a sci-fi-inspired sports game called Ballblazer as well as a primordial first-person shooter set in space called Rescue on Fractalus! To Schafer, these games were a revelation. The video game industry, on the whole, seemed almost magical.

“I was there at the beginning,” Schafer says. “I remember my dad bringing home a Magnavox Odyssey, the first home arcade console ever and just being so fascinated with it. Sometimes it feels funny to explain to people why it’s exciting to see things moving on a screen. I’m trying to talk to my daughter about it. She’s grown up with smartphones, and I’m like, ‘No, you don’t understand. TV was controlled by other people, and then you could make dots move on it!’ It was so fascinating.”

Schafer quickly became a video game fan. He devoured text adventures such as Zork, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, and Scott Adams’ Savage Island series. After his dad brought home a few Atari consoles as well as an Atari Computer, Schafer began experimenting with designing his own games, but he didn’t initially think about pursuing a job in the video game industry. In college, Schafer studied computer science, however, he was most passionate about creative writing. Authors like Kurt Vonnegut (Slaughterhouse-Five, Breakfast of Champions) were his icons, and he dreamed of being a writer.

“I thought I would write short stories and get a job at a database programming [company],” Schafer says. “All the jobs back then were database programmers … I loved video games, but, in my head, they were made by companies. I would think of Atari as, ‘Oh, it’s this big, monolithic building full of scientists and robots and some big, massive brain.’ But I realized later, ‘Woah, they were just young kids. They were young programmers all by themselves making these games.’”

One day, a friend told Schafer that Lucasfilm Games (rebranded to LucasArts in 1990) was looking for developers who could program and write. Schafer felt that he had unknowingly been preparing for a dream job his entire life. He thought back to the days he spent playing LucasArts games on his Atari, and he knew he didn’t want to pass up this opportunity. He just had to nail the interview.

“I had a bad phone interview with David Fox [the designer and programmer behind Rescue on Fractalus! and Zak McKracken and the Alien Mindbenders],” Schafer says. “He was really nice, but he asked me what Lucasfilm Games I had played, and I told him I really liked the games I had played on my Atari 800, like Ballblaster. He was like, ‘Ballblaster, huh? That’s what Ballblazer was called when it was pirated.’ [laughs] I was like, ‘Oh, God. He got me there because I had a disc of all their pirated games. Piracy’s bad, kids. Don’t do it. You’ll end up like me and have your own company and stuff.”

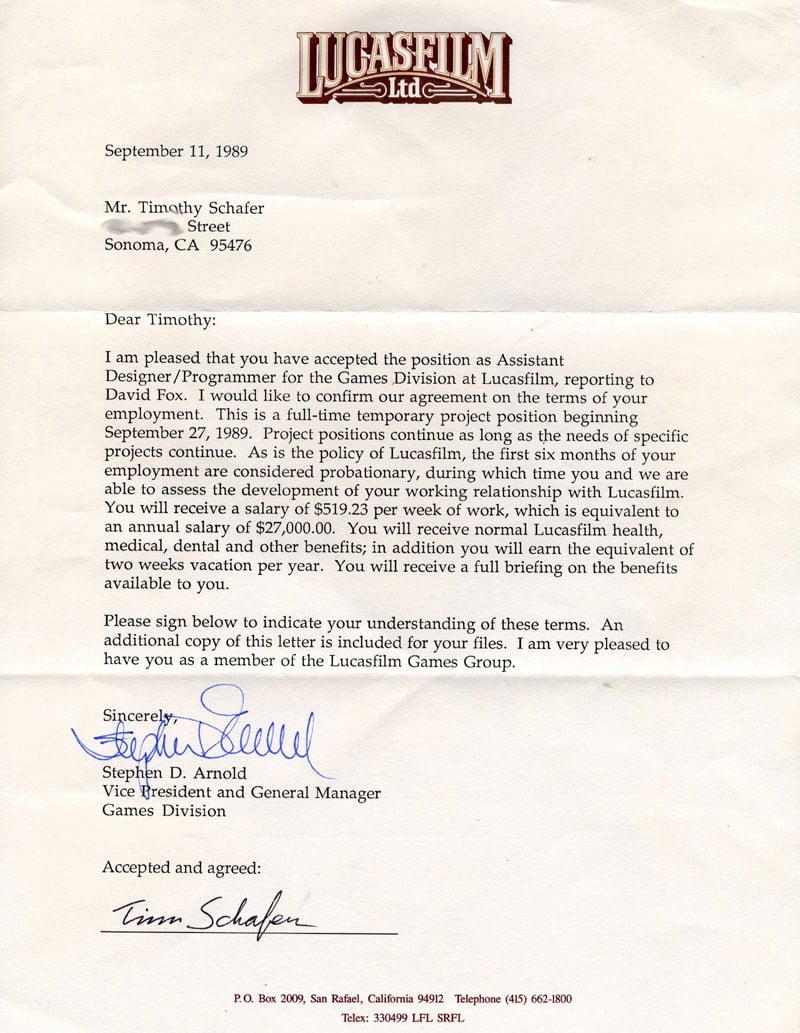

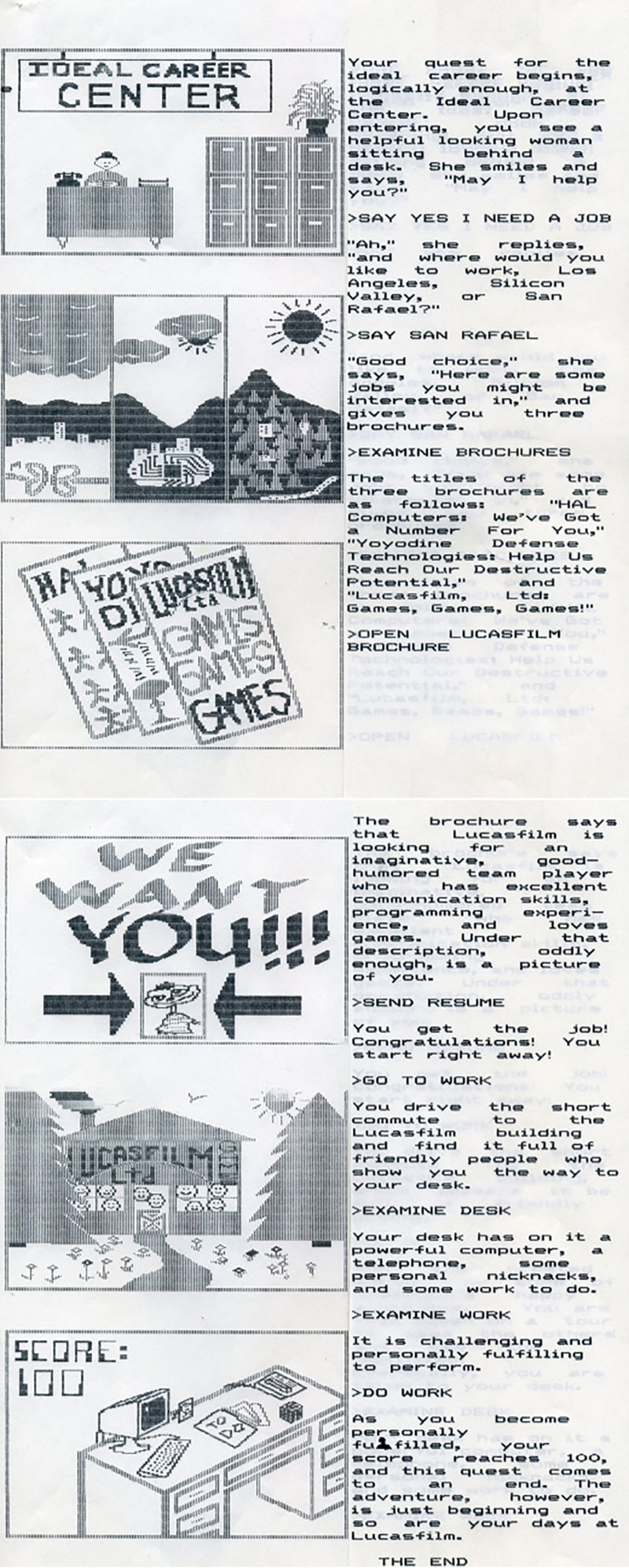

While Schafer was convinced he’d blown the initial interview, he wasn’t deterred, and spent several nights crafting a perfect cover letter/resume. In a cheeky nod to the job he hoped to one day attain, Schafer designed his letter to look like an early-’80s graphical adventure game complete with ASCII art depicting the Lucasfilm campus. Interview be damned, Schafer got the job.

A copy of Schafer’s cover letter to LucasArts, which helped him get the job

A copy of Schafer’s cover letter to LucasArts, which helped him get the job

Life On The Ranch

After the success of Star Wars, George Lucas built Skywalker Ranch near Nicasio, Calif., to function as his personal movie development workshop. The grounds contained an animal barn, outdoor swimming pool, fitness center, vineyard, and gardens full of fruits and vegetables for the onsite gourmet restaurant to use. When Schafer joined Lucasfilm in 1989, the campus also housed a motion picture mixing facility and served as the corporate offices for the studio’s many accountants and lawyers.

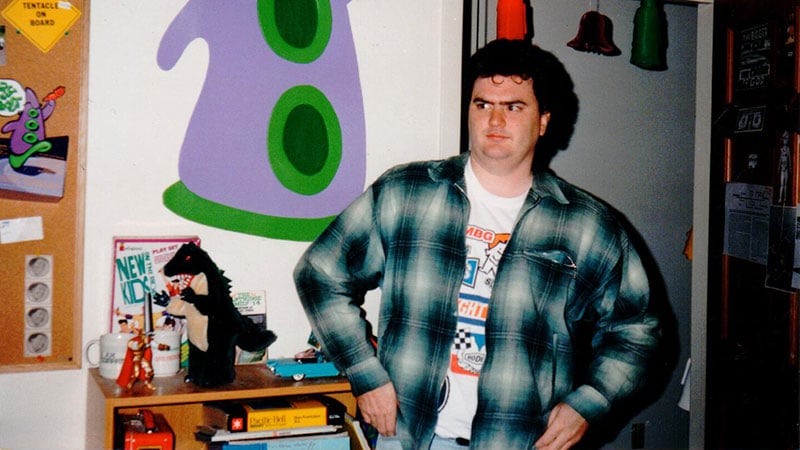

“It was amazing!” Schafer says. “I mean, right out of college, to go to work at Skywalker Ranch, you know? This was before Episode 1 was even imagined, so this was Star Wars in the magic times … there were a lot of celebrities around Skywalker Ranch. Jack Nicholson stopped by. Pearl Jam would record records there. At one point, Michael Jackson was at the Fourth of July picnic. You had to get used to like, ‘Don’t go up to people. Don’t bother them. Be cool around celebrities.’”

Schafer and his LucasArts family celebrate the release of The Secret of Monkey Island, which is still considered one of the most important adventure games of all time

Schafer and his LucasArts family celebrate the release of The Secret of Monkey Island, which is still considered one of the most important adventure games of all time

Lucasfilm’s computer and game division was tucked into the back of the Ranch’s facilities, but Schafer still found it to be a near-idyllic workspace. Over coffee breaks, he could walk out on the balcony and watch deer graze in the field. When he returned to his desk, he and his cohorts would joke around and talk about their favorite computer games. “It had a really well-funded startup kind of vibe, and then at lunch, you’d walk down to the main house, this beautiful Victorian, where there was gourmet food for $3 a day,” Schafer says.

However, Schafer’s time at the Ranch didn’t last long as some of the higher-ups at Lucasfilm eventually got fed up with the rowdy antics coming from the games team. “They kicked us out because games people do things that they don’t like at the Ranch, like ordering pizza at midnight and being a little bit rowdier,” Schafer says, laughing.

Schafer and the rest of the LucasArts team moved into the Kerner Complex in San Rafael, Calif. The building was also home to the movie special effects giant Industrial Light & Magic. At the time, ILM was working on films such as The Hunt for Red October, Back to the Future Part III, and Total Recall. The practical effects for many of these films required a lot of model work, and Schafer remembers watching scale figures of World War II bombers exploding outside his office windows.

Schafer in Die Hard 2

Schafer in Die Hard 2

“Fun things would happen,” Schafer says. “They’d be like, ‘Hey, anyone wanna be an extra? It pays 50 bucks. You’ll be an extra in Die Hard 2.’ We ran out there [at] 11 at night to 3 in the morning and just walked around this field with fake snow. They filmed us walking in different directions and put potato flakes on our shoulders.”