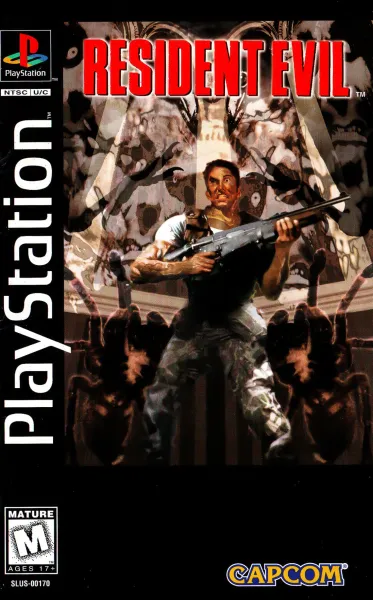

Ikumi Nakamura’s mother didn’t want her to work for Capcom. As she tells it, early in life, Nakamura saw a feature on the making of Resident Evil. In it, the game’s creators gather at a bar to drink and talk about the development. Nakamura’s mind was made up. She wanted to be a game developer. She wanted to work with the people she saw on screen. Nakamura’s mom was less impressed.

“I saw it, and I told my Mom, ‘Oh my God, I want to work with them,’” Nakamura tells Game Informer via translator. “And my Mom’s like, ‘No, don’t work with them. They’re just drunk, old men. Don’t do that!’”

Nakamura didn’t take her mother’s warning to heart.

Nakamura’s first job in the industry was at Capcom; she was an artist for its internal team, Clover Studios. That job meant a lot to her, personally. Aside from being a fan, Capcom’s games were something Nakamura bonded over with her father, which offered a personal connection to the work.

During and since, Nakamura’s had a hand in developing several cult-favorite video games, including Ōkami, Bayonetta, and The Evil Within series, working for Platinum Games and Tango Gameworks after Capcom. But for the majority of her career, she was relatively unknown within, and certainly outside, the game industry. That is until E3 2019, when her presentation for Ghostwire: Tokyo thrust her into video game stardom – thanks in no small part to her outgoing and offbeat personality. Nakamura has since become a social media favorite, befriending prominent game developers such as Sony Santa Monica’s Cory Barlog.

Nakamura is, more or less, an overnight sensation, and since leaving Tango and Ghostwire in September 2019, people have wondered what her newly founded studio is developing. Despite that, much of her story remains unknown – where she came from, her career at Capcom and Platinum, and her experiences at Tango. To remedy this, we reached out to Nakamura, and talked to her for hours – in one of her first big American interviews post-Tango – about everything from her love of horror to her once-daily nightmares while working on Ghostwire, to what she plans to do next.

Capcom

Growing up, Nakamura’s father kept one secret from her mother: He was bonding with their daughter over a shared love of horror movies and video games.

Nakamura’s father raised her the same way he would’ve raised a boy, and the two were both daredevils in their own ways. Where her father rode motorcycles, Nakamura climbed on the roof of her family’s house and jumped off their staircases. Which, to be fair, is a dangerous activity for a little kid, as evidenced by one of Nakamura’s childhood injuries.

“One day, I fell from the stairs and lost the lower part of my face,” Nakamura says, laughing, explaining she hit the ground face first. “The skin and the lower lip got dragged. It was almost like I lost my lower lip. My Mom saw it and she passed out from the shock, so no one could help me out at that time.”

Horror media made the biggest impact on Nakamura as a child. Nakamura and her father hid this from her mom, who didn’t approve, and they spent a lot of time watching scary movies and playing horror and gothic-inspired games together.

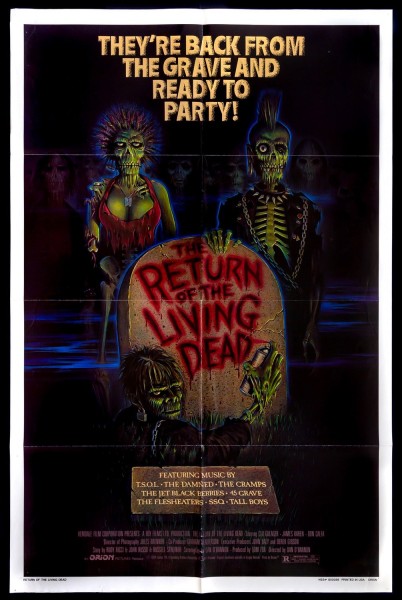

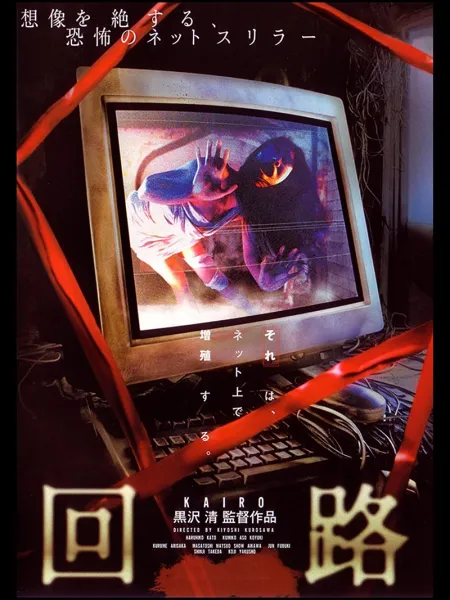

It can’t be overstated how profound an influence horror had on Nakamura; it’s something she constantly brings up when talking about her early life. Growing up, she says she watched horror movies every day, such as American classics like Return of the Living Dead. She also loved staples of Japan’s horror boom from the mid-to-late ’90s and 2000s, such as Pulse (Kairo in Japan), directed by Kiyoshi Kurosawa.

At the same time, as she puts it, Japan was in a “golden age” of video game development, and Capcom was just one of many companies spearheading that charge. Nakamura spent a lot of time playing games in the Resident Evil and Devil May Cry series – which, coincidentally, have been directed in the past by Shinji Mikami and Hideki Kamiya, who Nakamura would spend most of her career working alongside.

Nakamura went to art school in Tokyo and later the Amusement Media Academy to study game design. However, only a couple years into her education, her life was turned on its head. While out on his motorcycle, her father was in an accident and passed away suddenly, sending her life into “total chaos.” She spent a lot of her early life acting reckless, but Nakamura says her father’s death changed her, leaving her focused on protecting her family.

“After his death, I totally changed,” she says.

But one thing didn’t change: Nakamura’s dream of working at Capcom. If anything, her father’s death reinforced her desire to join the company after her schooling. He loved Capcom’s games, and during his funeral Nakamura made sure he was still able to play Resident Evil.

“In his coffin, I put a copy of the Resident Evil strategy book and a PlayStation controller,” she says. “[So] that he could play the game in another dimension. But I forgot that Japan is a cremation culture, so his bones and the controller got stuck together. I looked at it [as] he never gave up the game, even when he was a bone! I was impressed.”

Nakamura had to apply twice, but she joined Capcom in 2004, coming on board its internal Clover Studio. Initially set up to develop Viewtiful Joe 2, Clover was a semi-autonomous studio within Capcom’s Osaka, Japan headquarters, tasked with developing new intellectual properties. In line with Nakamura’s influences, Mikami and Kamiya worked as directors for the studio – the former overseeing 2006’s God Hand and the latter helping make Viewtiful Joe 2 and Ōkami, released in 2004 and 2006, respectively.

Nakamura’s first project was Ōkami. She joined Clover as a 3D environment artist – a job, she says, she was “incompetent” at. Despite her lack of experience, and the fact that some people within the company weren’t treating her well, Nakamura applied herself and tried to learn as much as possible on the project.

“I was new, I didn’t know really how to work, and was constantly told that I would be fired,” she says. “I was pushed around, overloaded with tasks and challenges. And so I went around to different sections, to ask about ‘how to work better’ and what I can help with, helping with anything I could, making animations or small stages, or objects.”

At the time, Nakamura describes Capcom as an “old-school” developer, full of behavior that wouldn’t fly in a modern workplace. For example, it wasn’t uncommon to see developers sleeping under their desks to save themselves a commute – something presented to the public on television in both Japan and the United States. When she was a kid, Nakamura says that when she saw that footage it seemed like a dream job. Now that she’s older, not so much. “[I felt like], ‘Oh my God, that’s what I wanna do,’” she recalls. “But then looking back, like, no, that is totally wrong.”

It also wasn’t uncommon for Capcom management to let their tempers get the best of them, lashing out and yelling at employees or hitting desks and kicking trash cans. “They would just kind of hit everything around them,” Nakamura says, adding that it showed her the kind of company culture she doesn’t want to create in the future, for which she’s thankful.

“Overall, it wasn’t effective,” she says. “People do get frustrated, that happens, but showing that physically or verbally, that creates fear in the work environment.”

“Now I know what not to do,” Nakamura says.

Ōkami

Ōkami

The relationship between Capcom and Clover was an acrimonious one, with constant clashes between management and Kamiya over Ōkami’s direction. According to Nakamura, her impression was that Capcom saw Clover as “just the group of weirdos” and a “totally separate entity.” As an example, she points to the Wii port of Ōkami, developed by Ready At Dawn, which didn’t include the names of the original developers or the Clover logo in the credits.

In 2008, Capcom issued a statement about the missing credits, saying the removal was due to a pre-rendered cutscene containing the Clover logo, which the publisher did not have the legal right to use in a game the studio wasn’t directly involved in. “We also didn’t have the source to the credit movie itself, so we couldn’t just use it and remove the Clover logo,” Capcom said.