Kyle Hudson didn’t know what Nintendo was. But it was 1988, he was just back from boot camp, and he needed a job. His friend, Jeff Palmer, suggested they both go work for Nintendo. Palmer’s cousin Cliff worked there as a gameplay counselor; he got paid to play video games all day. Hudson and Palmer could do that, too, the latter said.

“Jeff sold it to me like, ‘Hey, we’re gonna sit in a cubicle and play games all day and answer phone calls,’” Hudson recalls. “And I was like, ‘Hell yeah.’”

In 1987, Nintendo launched its Nintendo Power Hotline. If a player encountered problems beating a video game, they could call the hotline and get advice from what Nintendo called a gameplay counselor. It was effectively a call center. It was also so much more than that.

By the time Nintendo shut the hotline down in 2005, gameplay counselors had helped millions. It became a part of video game history, fondly remembered decades later by children that called. For some kids, gameplay counselors were heroes; they were literally people who got paid to play video games all day. For others, counselors were the first people in their lives to talk seriously with them about games. For many counselors themselves, the call center launched their careers – both within and outside of Nintendo. Despite not knowing what Nintendo was in 1988 when he applied, Hudson stayed with the company until 2012. More than two decades after taking his first call, he had worked his way up to Nintendo’s product testing manager.

To get an idea of what it was like to work at the Nintendo Power Hotline, we recently spoke with 12 people. Talking to a wide variety of former counselors and people that called the Hotline growing up, we got a fly-on-the-wall look at what it was like to be part of this point in Nintendo’s history. We also learned a lot about Nintendo of America’s culture in the ’80s and ’90s, spearheaded by its former president, Minoru Arakawa.

The Best Job in the World

Nintendo wasn’t picky about who could be a gameplay counselor. In the earliest stages, all a person needed was to show up at one of the many temp agencies employed to fill seats and complete an application. If the temp agency called back, the first interview was breezy.

“It was basically, ‘Can you work this shift?’ ‘Do you have reliable transportation?’ Just basic stuff,” Hudson says. “‘Are you breathing? Are you warm-blooded? Okay.’”

It was when people got to Nintendo that the process intensified. The company billed gameplay counselors as video game experts. If you had a problem with a game, the professional gamers in Nintendo’s Redmond, Wash. office could help you – no matter how complicated or niche the issue may be.

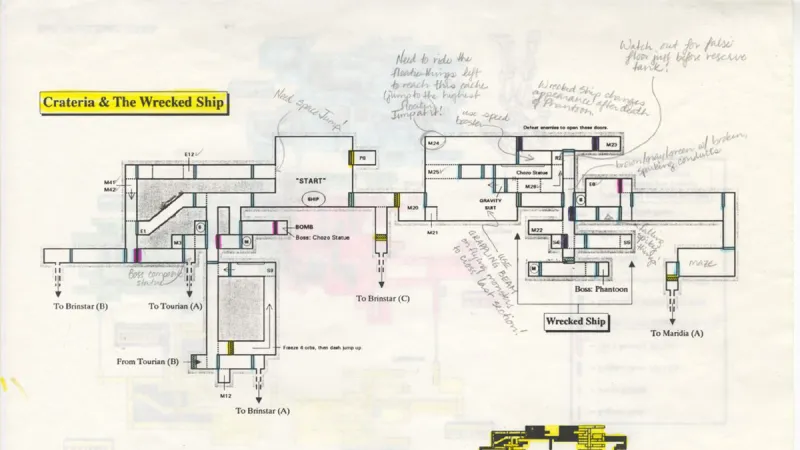

Hand-drawn map for Super Metroid that GPCs would use to help callers. Image: Stephan Reese/Art of Nintendo Power

Hand-drawn map for Super Metroid that GPCs would use to help callers. Image: Stephan Reese/Art of Nintendo Power

While Nintendo didn’t require any of its counselors to actually enjoy games, once a person made it past the initial temp interview, it did require a weeks-long training process. New employees had to play through games, learn about their various chokepoints and secrets, and take a massive test before they could field calls.

“Instead of just answering one very simple question about Legend of Zelda, maybe you have to list all of the treasures in all of the dungeons in both quests,” says former counselor Caesar Filori. “How do you get to the minus world in Mario? How many coins do you need for an extra life? They just wanted to make sure you actually knew the games inside and out, and the mechanics and how to beat the bosses.”

“But I’ll be honest with you. Myself, and a lot of people at that time, we cheated through the test,” Hudson admits. “Because I was like, ‘There’s no way I’m gonna remember all this s---.’”

After a short shadow period, where new counselors would sit in while an experienced counselor took calls, they finally got on the phones. Calls were immediate and plentiful.

It’s hard to nail down exactly how many calls a counselor would get on a given day, though most approximations land around 100 per shift. At its height, the call center had a couple hundred people taking calls for just under 24 hours a day. If each person is taking around 100 calls per day, in total, the call center was receiving thousands of calls every day it was in operation. Sam Hosier III, who worked there between ’94 and ’97, says at one point Nintendo gave out a shirt “that said we had done 28 million calls.”

Of course, this number was exacerbated by the holiday season, when people across the country were getting new Nintendo games and consoles. The counselors dubbed this “Hell Week.”

“When we had our full call center, they put up these telecaster boards that showed you how many calls were in-queue,” former counselor Yvette Kirby Waters says about Hell Week. “We called it the ‘Hellecaster’ because you could feel the pressure when 100, 200 calls are in-queue – 300, you know? And there were over 100 people in the call center taking calls one after another – boom, boom, boom. And yet, the queue list is still in the hundreds.”

Even though Nintendo required a certain level of memorization and expertise, it was understood gameplay counselors couldn’t know everything every one of those millions of callers inquired about. To help with tough calls, each counselor had a large green binder full of notes, hand-drawn maps, and solutions. Get good enough at passive conversation, and a caller on the other end of the line would never know a counselor was quickly flipping through pages, trying to find an answer. To them, it might seem like this person is the all-knowing gamer Nintendo was pitching them as in its then-monthly magazine Nintendo Power. In each issue, individual counselors were highlighted in the “Counselors’ Corner,” featuring tidbits such as their highest game score and favorite Nintendo games, letting callers put faces to the voices on the Nintendo Power Hotline.

Despite the sheer number of calls, as every counselor we talked to tells it, after long enough working the phones, you start to identify the most common questions across Nintendo’s most popular games. They may have taken over a hundred calls a day, but most of those calls were about the same two or three games. Work there long enough, and you can spend a lot of your day on autopilot.

“Once you heard the question, the response coming out of your mouth, you really didn’t have to think about it,” Hudson says.

This left gameplay counselors a lot of time to play video games on the clock – somewhat making good on the dream kids had that these were people who got paid to play games all day. In the Nintendo office was an ever-growing library with every single game the company had released up to that point. “There were no gaps in the collection,” Hosier says.

Counselors could check out various titles, and their desks even had TVs and consoles where they could play games while taking calls.

“One of the risks that you have doing that is if you’re someone who emotes when you die when you play a game, that can become problematic,” Filori says, adding employees got good at muting the call. “I don’t remember who it was, but I do know for fact a time where somebody got the mic button muting reversed, so all the person heard on the other end was profanity.”

Gaming in the office led to many now-famous pictures. While, ostensibly, letting counselors play games on the clock was so they could stay up-to-date and familiar with all Nintendo’s games, these photos worked double-duty as great recruitment tools. Kids could see counselors sitting in an office cubicle, making money and playing games. Who wouldn’t think that was cool?

“The concept of gameplay counselors back in the day for a kid obsessed with Nintendo games was kind of this dream job,” Phil Theobald, who called the hotline as a kid, says. “In my head, I had this vision of gameplay counselors as, like, the best job in the world.”

There were, however, the “nightmare calls.” For example, The Goonies, based on the movie of the same name, released by Konami in 1986. As Filori tells it, most of the areas in the game look identical; it was near-impossible to identify where a player was stuck. Same with Legacy of the Wizard. HAL Laboratory’s 1989 puzzler Adventures of Lolo was another pain point for gameplay counselors.

“I mean, these are like the Candy Crushes of the time,” says former counselor Casey Pelkey about Lolo. “People would call, and they’re in, like, the 11th level or something like that. They’re like, ‘Give me step-by-step.’ And we’re talking block by block how to do something. It can take forever, and as soon as they do something wrong, it’s a reset, right? Let’s try it again.”

“Lots of people would hang up on those calls,” Filori says. “Then, because the supervisors could still hear what you’re saying, even once you’ve wrapped up [since they would monitor calls for quality], they would just keep talking. They’d hang up and keep talking and then say like, ‘Um, are you still there? Are you still there? Hello? Hello?’”