I'm two floors below ground, surrounded by screaming drunks and breathing in enough secondhand smoke to take at least a decade off my life. I'm here with Keiichiro Toyama, most well-known for creating the Silent Hill series, but also the creator of the Siren and Gravity Rush series, and most recently, the founder of Bokeh Game Studio, making the upcoming Slitterhead.

A cramped, old, smoky bar in a shopping mall deep beneath a Yokohama train station might not immediately appear conducive to game development, but things are starting to click in my head. Mixed with pounds of nicotine, the air in the bar is communal and light. It's also distinct compared to the more modern, formulaic streets immediately above our heads. In an hour or two, we'll walk a few blocks over and hit the nightlife and drinking alleys. Tucked within the immensely larger Tokyo surrounding them, these areas have their own distinct senses of space, much like the worlds of Toyama's games. He's been living in Yokohama for decades, he tells me. Something like Gravity Rush – with its unforgettable, topsy-turvy, boozy, and somewhat seedy world – makes a lot more sense to me now.

I'm in Japan to learn about just that; how where you live affects what you make. This time, it's through the lens of one single developer: Bokeh. For three days, I spend time with Toyama, concept artist Miki Takahashi, and renowned composer Akira Yamaoka in vastly different parts of Tokyo, learning about the city's ever-changing face, what they love and what they miss, and how decades of living here have influenced their works all the way up to Slitterhead.

First stop: a former black-market and well-known place to drink the night away.

Photo courtesy of Keiichiro Toyama

Photo courtesy of Keiichiro Toyama

RUNNING THROUGH THE STREETS WITH KEIICHIRO TOYAMA

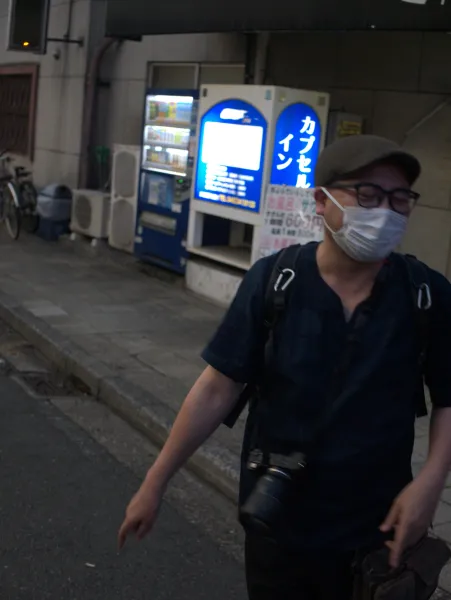

Toyama is darting – somewhat carelessly – across the streets of Noge, Yokohama, taking pictures of whatever he finds interesting while Bokeh PR and business development manager and translator William Yohei Hart and myself try to keep up. Toyama's had a few drinks. It helps him socialize, he says. And now he truly seems in his element.

An hour earlier, we were talking in the smoky, boozy halls of Sakuragicho Pio City, an underground shopping mall right next to Sakuragicho Station. It feels spat out of a different era – mainly because it is. The yellowed walls and slick tile floors feel familiar, if a little dirty. It's like we’ve been transported back to the 1990s, as if time stopped below the modern streets above our heads.

Toyama takes me to Pio City to visit an izakaya – or an all-you-can-eat-and-drink bar. We huddle around our tiny table while older men chain-smoke cigarettes and drink beers. Toyama orders highballs. A mix of beef, lamb, and cooked vegetables comes out for us all to share. The restaurant is loud but in a friendly way. Customers laugh drunkenly, and the staff runs around frantically yelling to the cooks in the back while running out orders. It is, put bluntly, a perfect place to come and get drunk with friends, filling your stomach with as much alcohol and grease as your body can handle.

"I just love drinking," Toyama tells me. "I just love the setting. I'm not a big alcohol lover; in terms of I don't really care about the taste. It's more about the atmosphere of these places."

Toyama moved to Yokohama – the second largest city in the country by population and part of the Greater Tokyo Area – after Silent Hill came out in 1999. Even after all this time, he finds Noge exciting. It's directly influenced his work on the Gravity Rush series and the upcoming Slitterhead.

Noge traces its history back to post-World War II Japan, when, in an effort to get away from American-occupied parts of nearby areas, people fled to the area. It became a bustling black market, where at one time, there were reportedly more than 400 stalls along the area's main street. Noge has also been a popular destination for jazz artists, and there are still plenty of jazz bars in the area today. Over time, Noge became a popular nightlife district, attracting people from all walks of life who want to eat and drink as much as possible before shambling home for the evening.

The open atmosphere is what Toyama finds inspiring. Japan, especially compared to, say, America, is an incredibly safe country. But around these parts, where the atmosphere is looser, he likes that anything can happen.

"Even if it's a drunk that's just rolling on the floor – I just feel a bit excited about that," Toyama tells me.

In Gravity Rush and Slitterhead, he says he thinks you can see an area like Noge's influence. People walk around the game cities talking openly, hanging out, and having a good time. Similar to this izakaya, where just like beer and food, conversations flow endlessly from one topic to the next.

That said, Toyama is, self-admittedly, a shy person. He has trouble talking to people sometimes, and I notice he's not big on eye contact and directs all his responses to Hart rather than me. Alcohol helps. While we hang out, Toyama drinks two large glasses of Highball. He says he needs a few drinks – especially with a journalist – to open up and talk freely.

"In an ideal world, I wouldn't have to do any media or any interviews. In that world, I'm completely free," he admits. "But as a CEO of a company now, I have to be more outgoing, and [I have to] socialize around the world. That part needs some drinks."

This makes me think Toyama is more of an observer of the atmosphere around him rather than an active participant. It makes sense when you consider how he makes his games.

"When I think of a game, what I do first, I think about the environment rather than characters or story; I think you can see in Gravity Rush all these places that I drew inspiration from," he adds. "Because when you think of a town or a village, and you think about an ordinary person in that village or town, you get to imagine a backstory about what an ordinary person's life is like in that place. Which is why it helps to think about characters who are born in that setting. It helps me to think about a story that way better than thinking about a story first."

Photo courtesy of Keiichiro Toyama

Photo courtesy of Keiichiro Toyama

To capture those settings, Toyama brings his camera with him everywhere he goes and takes pictures of anything he finds fascinating – from beautiful scenic views of the city all the way down to our dinner table. On the one hand, this is obviously his favorite hobby – and a way to quickly gather reference material for his work. On the other hand, as he says, it's like his own personal time machine. When he looks back at photos he took years ago, he immerses himself in that exact moment like he's traveling back in time. No matter what in the city changes or disappears, he always has the photos he takes. In turn, his games all have a strong sense of place. It's easier to remember specific districts or pockets of his worlds than the characters inhabiting them.

Part of that is he misses how Japan used to be. This is largely the reason he brought me to Noge; it reminds him of how the city was 25 years ago. "I have a lot of love for things that are disappearing," Toyama tells me. He's a nostalgic person; he's attached to the past.

He recognizes Japan's ever-changing face is partly due to the country's high level of earthquakes – more than any other country in the world. Older buildings don't meet modern codes and are torn down to protect citizens. A somewhat ironic fate of killing the past to save the future. But still, Toyama, now in his 50s, loves Noge because it reminds him of an era long since gone – Japan's economic miracle.